K2 - 8611m - #2 In The World

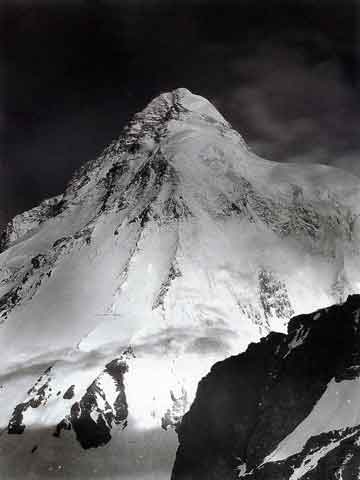

K2 (8611m) is the second highest mountain in the world, and is thought by many climbers to be the ultimate climb. It is much more difficult and dangerous than Mount Everest. Its giant pyramid peak towers in isolation, 3900m above the wide Concordia glacial field at the head of the Baltoro Glacier. In 1856 Capt. T.G. Montgomerie of the Great Trigonometric Survey of India saw a cluster of high peaks from a point 137 miles away in Kashmir, and entered them as K1, K2, K3 and so on, with K standing for Karakoram. K1, K3, K4 and K5 were eventually renamed Masherbrum, Broad Peak, Gasherbrum II and Gasherbrum I respectively. But, K2 kept the surveyor's notation as its common name.

The mountain's remoteness had rendered it invisible from any inhabited place, so apart from an occasional local reference as Chogori (meaning Great Mountain or Big Snow Mountain), it had no other name prior to Montgomerie's survey. Since that time, the name Mount Godwin-Austen has occasionally been used, in honour of the man who directed the survey. For the most part, however, K2 has been the name of choice, and has even evolved into Ketu, the name used by the Balti people who act as porters in the region. The sheer icy summit is flanked by six equally steep ridges. Each of its faces presents a maze of precipices and overhangs.

The Karakoram (“Black Mountains”) and Himalaya are the newest mountains in the World. Pakistan has the largest concentration of high mountains in the World. There are more than 100 peaks over 7,000 meters within a radius of 180 kilometers. Five of the 14 8000-metre peaks in the world are in Pakistan. Peaks above 3,000 to 6,000 meters are countless and remain unclimbed and unnamed. Out of 100 highest peaks in the world, more than 50 are in Pakistan.

Jim Wickwire from the Foreword for the book Five Miles High:

"For many climbers K2 – even more than Everest – is the ultimate mountain. At 28,250 feet, it is second only to Everest, a scant 800 feet higher. With its classic pyramidal shape, K2 is steep on all sides. It is the perfect embodiment of our mental image of what a great mountain should be like. The climber who has designs on K2’s summit must not only content with extreme altitude and difficult rock and ice, but with sudden storms that deplete strength and erode willpower."

Jim Curran describes his first view of K2 in his book K2 Triumph and Tragedy:

"The sight made my flesh crawl, and took away what little breath I had. K2. There it was, unequivocal, real, present, impassive and quite momentarily huge. A great triangle that hung like a gigantic backdrop to the silent amphitheatre of Concordia."

Baltoro Glacier Trekking Route To Concordia And Gasherbrum Base Camp

After flying from Islamabad to Skardu with an amazing view of Nanga Parbat, driving from Skardu to Thongol, and trekking from Thongol to Paiju, I set foot on the Baltoro Glacier. I trekked to Khoburtse that first day with a stunning view of Trango Nameless Tower and the Great Trango Tower. I had a dazzling sunrise from Khoburtse with views of Paiju Peak, Uli Biaho Tower, Trango Towers, Cathedral, and Lobsang Spire. The next trekking day we went from Khoburtse to Goro II where Masherbrum was striking both at sunset and sunrise while Gasherbrum IV loomed ahead with Gasherbrum II poking out to its right.

The next day was a fairly short trekking day passing Muztagh Tower before arriving at Concordia, the highlight of the whole trek with K2 dominating the view at the head of the Godwin-Austen Glacier. Rotating in a circle at Concordia, the view has K2, Broad Peak, Gasherbrum IV, Baltoro Kangri, Vigne Peak, Mitre Peak, Paiju Peak, the spires of the Baltoro Glacier, Crystal Peak and Marble Peak. WOW! Spectacular! Breathtaking!

The next day we trekked on the Upper Baltoro Glacier to Shaqring Camp with views of Chogolisa and Baltoro Kangri. Cloudy weather rolled in as we trekked on the Abruzzi Glacier to Gasherbrum Base Camp with a brief view of Gasherbrum I. After back-tracking to Concordia it snowed, so we decided to return back down the Baltoro Glacier instead of waiting for the weather to clear and the snow to melt.

K2 North Face Trek Route And Gasherbrum North Base Camp

After flying from Beijing to Urumqi and Kashgar, we drove to Karghilik and finally to Yilik village (3504m). The trek was easy to Sarak Camp (3759m) and Kotaz Camp (4330m) before crossing the Aghil Pass (4810m) and descending to the Shaksgam Valley (4000m). The trail was along the wide expanse of the Shaksgam River to a beautiful camp at Kerqin (3968m) with small flowers and mountain views. The trail to K2 Base Camp continues on the flat Shaksgam Valley to River Junction Camp (3824m) and then to the Sarpo Laggo Valley and Sughet Jangal (3900m). The trek was fairly short to K2 Intermediate Base Camp (4462m) with spectacular views of K2 North Face, especially at sunset. I was the only person at this lonely camp.

I retraced the trail back to River Junction and Kerqin camps, passed the valley from Aghil Pass and continued to Kulqin Bulak Camp (4060m) and Gasherbrum North Base camp (4294m) with breathtaking views of Gasherbrum I, Gasherbrum II and Gasherbrum III. We then retraced to Yilik Village and back to Kasgkar and Beijing.

K2 1892 and 1902

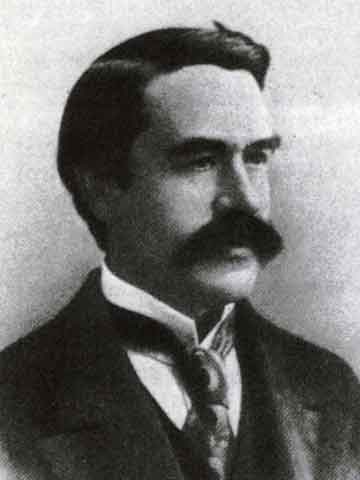

Excerpt from Climbing The World's 14 Highest Mountains by Richard Sale and John Cleare: In 1892 the base of the peak was reached for the first time by the British mountaineer Martin Conway. Conway explored the Baltoro, naming Concordia ... and discovering the Godwin-Austen and Vigne Glaciers. Conway also named Broad Peak and Hidden Peak (Gasherbrum I). Conway's team made an attempt on a peak he called Golden Throne (Baltoro Kangri) reaching a subsidiary summit. Although Conway's expedition did little actual climbing, in terms of exploration it was a major success.

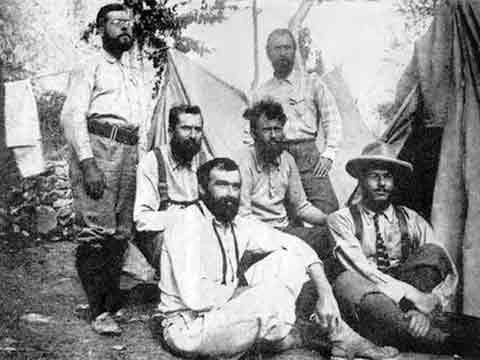

Ten years after Conway's trip [in 1902] a small team of British and Austrian climbers and a Swiss doctor under Oscar Eckenstein arrived to climb K2. ... Eckenstein doggedly refused to deflect from his objective, with the result that the team did not get higher than 6,600m and then had to retreat hastily when [Heinrich] Plannl contracted pulmonary oedema. ... The expedition was also notable for including Edward Alexander (Aleister) Crowley, the self-proclaimed Great Beast 666 etc. whose abilities as a climber have been completely overshadowed by those as a self-publicist, though they actually seem to have been far greater than his abilities to conjure up the Devil.

K2 1909 Italian Duke Of Abruzzi Expedition

Wikipedia: The next expedition to K2, in 1909, led by Prince Luigi Amedeo, Duke of the Abruzzi, reached an elevation of around 6,250 metres (20,510 ft) on the South East Spur, now known as the Abruzzi Spur (or Abruzzi Ridge). This would eventually become part of the standard route, but was abandoned at the time due to its steepness and difficulty. After trying and failing to find a feasible alternative route on the West Ridge or the North East Ridge, the Duke declared that K2 would never be climbed, and the team switched its attention to Chogolisa, where the Duke came within 150 metres (490 ft) of the summit before being driven back by a storm.

The Duke's team included Vittorio Sella, arguably the greatest mountain photographer of all time

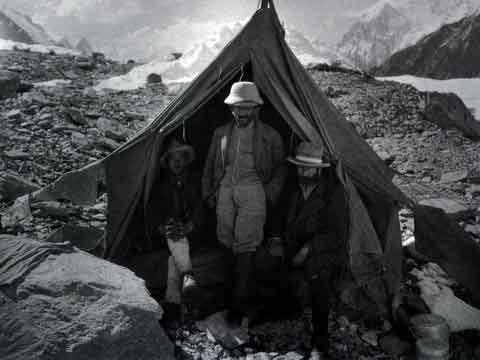

K2 1938 American Expedition

The 1938 American Karakoram lightweight expedition of 6 climbers and 6 porters travelled from Srinagar to Skardu by ponies and then trekked from Skardu to Base Camp. They explored five main ridges: the Northwest and West ridges from the Savoia Glacier, the Southwest from the Angleus, the Southeast Abruzzi ridge, and the Northeast. And then settled on the Abruzzi Ridge as the most feasible.

Bill House climbed a great slanting gash in an almost vertical rock to surmount the first main difficulty of the Abruzzi Ridge, now called House's Chimney. House: "With feet and hands gripping both sides, I climbed up 20 feet to where the walls flared outward and became so smooth that I had to put my back against one and feet against the other to hitch myself up a few inches at a time."

Houston and Petzoldt overcame the second main difficulty of the Abruzzi Ridge, they called the Black Pyramid. Houston: "We felt that the last thousand feet leading onto the great shoulder was by far the most difficult and inaccessible stretch of all. ... Shortly after noon we shook hands at the top of the Black Pyramid at an altitude of approximately 24,500 feet. Abruzzi ridge had been conquered and we had found a route to the snow fields of the 25,000-foot shoulder."

With the summit within their grasp, the team decided that safety came first, so they agreed that Houston and Petzoldt would continue climbing for only three days. Houston: "At last, at the base of the final cone, I could go on no farther. Petzoldt was 150 feet above me, working on the rock. ... A deep and heartfelt regret at abandoning the attack, when success seemed within our grasp." Excerpts from Five Miles High by Robert H. Bates and Charles H. Houston.

K2 1939 American Expedition

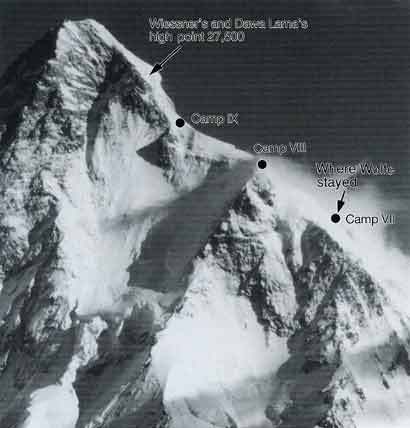

In 1939 another American expedition, this time led by Fritz Wiessner, came within 200m of the summit, but ended in disaster when four climbers disappeared high on the mountain. After the best climbers dropped out, Fritz had to lead an inexperienced and weak team. Fritz led all the way, breaking trail, and turned back at 8380m just below the easy summit snowfield when Pasang Lama wouldn't go on. After a second attempt failed because Pasang had lost his crampons, Wiessner and Pasang descended to Camp VIII, only occupied by Dudley Wolfe.

On the descent the three climbers fell, but Wiessner was able to self-arrest, stopping their fall. Ed Viesturs thinks that "only Pete Schoening's 'miracle belay' in 1953 is more legendary than Wiessner's self arrest." Unknown to Wiessner, all camps below camp VIII had been stripped supposedly because they thought that the summit party had been killed. The attempt to rescue Wolfe failed, with Wolfe and three Sherpas perishing on the K2 Shoulder. Ed Viesturs thinks that "any climber has to be in complete awe of Wiessner's performance on K2." and considers his logistical plan "brilliant." Excerpts from K2: Life and Death on the World's Most Dangerous Mountain by Ed Viesturs and David Roberts.

K2 1953 American Expedition

After their 1938 reconnaissance expedition, Houston and Bates returned to K2 in 1953 to attempt the summit. They climb the Abruzzi spur, carrying their own loads, using a pulley on House’s Chimney. They slowly set up camps, and on August 2 eight mountaineers are in Camp VIII, ready to attempt the summit. "Morale was magnificent. We were within striking distance of the goal. The summit might still be ours." But then in shades of the 1986 K2 tragedy, a storm hits and they have to remain at Camp VIII for seven days However, on August 7, "As Art Gilkey crawled out to join us, he collapsed unconscious in the snow. ... Art had developed thrombophlebitis. ... There was no hope, absolutely none. Art was crippled. He would not recover enough to walk down. We could not carry him down. But we could try, and we must."

They wrapped Gilkey in a sleeping bag and began lowering him down towards Camp VII on August 10, changing the route to a rocky cliff to avoid avalanche danger. "I never saw Bell fall, but to my horror I saw Streather being dragged off the slope ... In almost the same instant I saw Houston swept off ... a terrible jerk ripped me from my hold." Three separate ropes luckily got tangled together as the five men fell. "the whole strain of the five falling men, plus Gilkey, was transmitted to Schoening. ... a solitary ice axe with its pick end jabbed into the ice. ... One man had held five men who slid 150 to 300 feet down a 45-degree slope and that he had done it at nearly 25,000 feet"

They anchored Gilkey and went to Camp VII to set up the tents. When they went back to get Gilkey, an avalanche had ripped him from the anchors, "The whole slope was bare of life. Art Gilkey was gone!" The descent was harrowing in stormy conditions and with Houston in shock from a concussion, and Bell with frostbite in his feet and hands. They set up a memorial cairn to Gilkey near Base Camp. "Except for the dull ache of Gilkey’s loss, we felt at peace with the world. ... We had done our best and had survived." Excerpts from K2: The Savage Mountain by Charles H. Houston and Robert H. Bates.

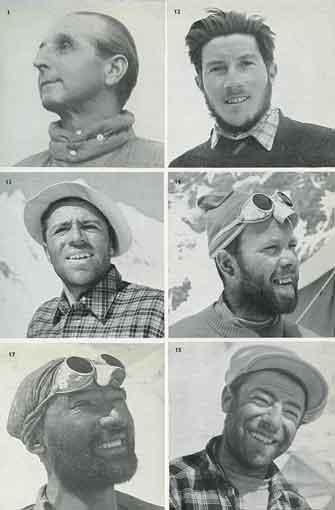

The first ascent of K2 was completed by the 1954 Italian Expedition led by Ardito Desio. After studying the previous K2 attempts, especially learning from the 1953 American expedition, and making a reconnaissance of K2 with Ricardo Cassin in 1953, the first controversy struck the expedition when Cassin was dropped from the team. Tragedy hit the expedition when Mario Puchoz contracted pneumonia (now thought to be pulmonary oedema) and died on June 21.

Desio pushed the team on, "The honour of Italian mountaineering was at stake.", and assigned Achille Compagnoni as the leader on the mountain. Compagnoni and Lino Lacedelli climbed up to Camp IX on July 29, with Walter Bonatti and HAP Mahdi following, carrying their oxygen bottles. But Compagnoni intentionally moved the camp from the planned site so Bonatti could not try for the summit. After waiting in vain for Lacedelli and Compagnoni to appear, Bonatti and Mahdi had to suffer through a bivouac at 8100m, with Madhi suffering frostbitten toes.

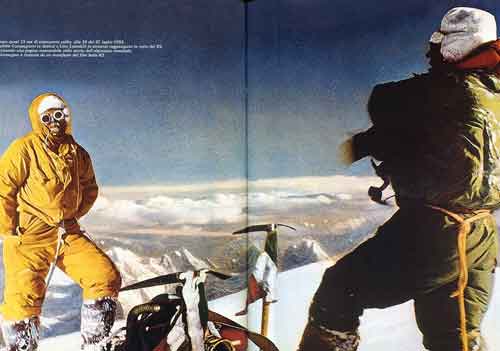

After Bonatti and Mahdi descended at first light, Lino Lacedelli and Achille Compagnoni picked up the oxygen and continued, reaching the summit of K2 at 6:10pm on July 30, 1954.

"The ground was almost flat - now it was flat! We looked about us ... Above us there was nothing but blue sky ... We embraced each other, then flung ourselves down flat on the snow so that we could remove our oxygen-masks. Next we tied the two small flags – Italian and Pakistani – to an ice-axe, together with a small standard of the Italian Alpine Club." While Compagnoni gushes with personal satisfaction, "it would probably be true to say that we had both just experienced the greatest moment of our lies", Desio hits the nationalistic tone: "Lift up your hearts, dear comrades! By your efforts you have won great glory for your native land ... to-day all Italians are rising to acclaim you as worthy champions of your race." – from Ascent Of K2: Second Highest Peak In The World by Ardito Desio.

A 50-year controversy struck when the expedition leaders accused Bonatti of turning back before delivering needed oxygen to the lead climbers below the summit. After staying quiet for 50 years, Lacedelli finally published his view of what happened in 2004, corroborating Bonatti's story.

K2 First Ascent Northeast Ridge

The long, corniced K2 Northeast Ridge was climbed for the first time by an American team led by Jim Whittaker in 1978. John Roskelley and Rick Ridgeway led the most difficult section of the northeast ridge. "We were climbing on the edge of a knife. The slope dropped away on both sides, steeply, dramatically, to glaciers thousands of feet below. ... Twelve hundred feet of steep ridge was behind us, fixed with rope."

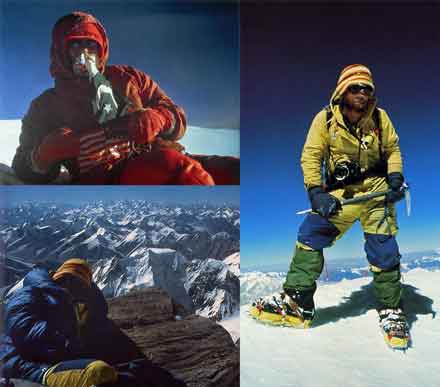

After reaching their top camp, Jim Wickwire and Lou Reichardt decided to try the Abruzzi, while John Roskelly and Rick Ridegeway attempted the direct route to the summit. John and Rick had to turn back due to avalanche danger. Lou Reichardt and Jim Wickwire reached the K2 summit on September 6, 1978 at 17:15pm. "The summit of his dreams, Wick stared across the mountains stretching endlessly below him, summit after summit painted gold. They were all below him. The world curved away, in all directions, falling away, below his feet. For Lou, it was an even more remarkable victory. He was the first man to climb K2 without oxygen."

Lou quickly left the summit at 17:30 and reached Camp 6 late that evening where John and Rick were planning their ascent. Wick lingered until 18:15 on the summit and had to suffer through a horrible bivouac just below the summit. Wick: "What a place this would be to spend an eternity. Frozen up here forever on the summit of K2. The highest man in the world. ... Be careful. You’ll be down soon. I’m coming home, Mary Lou. I love you." Wick was able to descend, but eventually got pneumonia complicated with pleurisy and had to take a rescue helicopter near Paiju. Rick Ridgeway and John Roskelley reached the summit the next day, on September 7 at 15:30 without oxygen. "No wind. No Clouds. Cerulean sky, brilliant sun ... Nothing quite real, the feeling of a dream. ... John crawled up behind me, and together we sat on top, holding each other, too exhausted to speak." Excerpts from The Last Step: The American Ascent Of K2 by Rick Ridgeway.

K2 First Ascent West Face

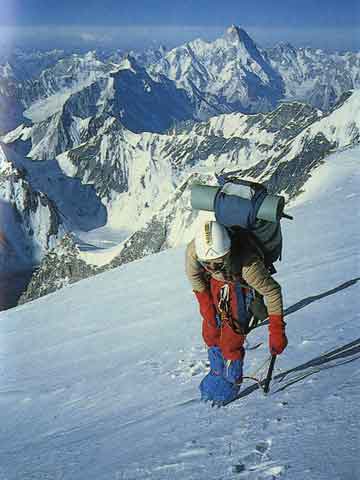

The K2 West Ridge, 3200m of ice and rock, was first climbed by a Japanese expedition led by Teruo Matsuura in 1981, with Eiho Otani and Pakistani Nazir Sabir reaching the K2 summit on August 7, 1981. Excerpt from Climbing The World's 14 Highest Mountains by Richard Sale and John Cleare:

They followed a snow band across the west face to the top of the south-west ridge. The route, which was fixed with 5,500m of rope, had taken 52 days to climb. On 6 August Eiho Otani, Matsushi Yamashita and Nazir Sabir climbed the fixed ropes to the south-west ridge and started for the summit. ... By 6pm they had climbed to about 8,470m where they decided to bivouac.

Next morning, 7 August, they climbed another 100m ... just 50m from the top. Here Otani and Yamashita radioed the team leader and were told to descend as they were too tired to continue. Sabir ... was appalled. After 45 minutes of sometimes heated argument the leader eventually agreed they could continue. Yamashita was by now too exhausted to continue, but Otani and Sabir climbed on, reaching the top an hour later.

K2 First Ascent North Ridge

The difficult North Ridge on the Chinese side of K2 was climbed for the first time in 1982 by a team from the Mountaineering Association of Japan, led by Isao Shinkai and Masatsugo Konishi. Naoe Sakashita, Hiroshi Yoshino, and Yukihiro Yanagisawa reached the summit on August 14, 1982. Yanagisawa fell and died on the descent. The next day Hironobu Kamuro, Haruichi Kawamura, Tatsuji Shigeno, Kazushige Takami also reached the K2 summit.

Excerpt from K2: A Challenge To The Sky written by Kurt Diemberger: The North Ridge and its lateral glaciers taper towards the summit in a single, increasingly steep line, uninterrupted by the terraces and shoulders which characterize the South-East side, on the Abruzzi Ridge. As it approaches the peak, the crest breaks up into steep towers and pinnacles, and on more than one occasion the Japanese climbers tried to move onto the hanging glacier on the left-hand side. A complex and difficult manoeuvre was necessary and was eventually completed at an altitude of 8,000 metres. Both of the Japanese climbing teams exploited the very steep glacier and the ribs to either side to reach the summit.

K2 First Ascent South Face

The K2 South Face (Central Rib), called a suicidal route by Reinhold Messner, was climbed for the first time on July 8, 1986 by Jerzy Kukuczka and Tadeusz Piotrowski. Excerpt from Climbing The World's 14 Highest Mountains by Richard Sale and John Cleare:

... they established an equipment dump at 7,000m. After a ten-day delay due to bad weather Kukuczka and Piotrowski returned to the face. It took two days to reach their dump, two more to reach the final headwall. On this they also spent two days, on the first of which Kukucxka, in the lead, climbed only 30m of what he later described as the hardest climbing he had ever done at altitude. At their bivouac, the Poles dropped their last gas cylinder, but used a candle to melt a mug of water.

The next day they summited and descended towards the shoulder but were forced to bivouac again. Now, in appalling weather and badly dehydrated they continued to descend towards the camps on the original route, but Piotrowski lost his crampons and immediately slipped off the mountain.

K2 First Ascent South-southwest Ridge

The K2 South-SouthWest ridge, called the Magic Line by Reinhold Messner in 1979, was climbed for the first time by Wojciech Wroz, Przemyslaw Piasecki and Peter Bozik on August 3, 1986. Excerpt from K2: A Challenge To The Sky by Roberto Mantovani:

One of the great routes (2,300 metres difference in height from the Negrotto Saddle to the summit of K2), aesthetically very attractive, logical and difficult. Casarotto climbed alpine style, without installing fixed ropes. ... On the afternoon of the 7th of July, Renato reached 8,300 metres. A single day of fine weather and he would have gained the summit. It was not to be.. ... On the 16th of July he made another attempt before turning back.

... Following Casarotto's death, the ridge was climbed by the Poles Przemyslaw Piasecki and Wojciech Wroz and the Slovenian Petr Bozik. They reached the summit of K2 on the 3rd of August. The climb contained sections with IV and V level difficulty ratings on rock, and notably steep slopes on snow and ice. It required the installation of long stretches of fixed ropes, three high altitude camps and two bivouacs at 8,000 and 8,400 metres. Having reached the summit in the late afternoon, the climbers decided to descend along the normal route. Wroz fell to his death at half past eleven at night, whilst negotiating a difficult section at 8,100 metres.

K2 First Ascent South-southeast Cesen Spur

Doug Scott, Roger-Baxter Jones, Jean Afanassieff and Andy Parkin climbed the south-southeast spur to just below the Shoulder on July 23, 1983. Excerpt from Doug Scott Himalayan Climber: We were all keen to climb K2 alpine style by a new route and the South Rib looked the ideal objective for this. ... As we got higher the deep snow and icy winds made trail-breaking very arduous. There was also some avalanche danger, so for our fourth bivouac we stopped in a safe position under rocks 100m below the Shoulder. On the fifth day, at about 7500m, Jean announced that he was suffering various symptoms of altitude sickness. ... we descended rapidly and regained Base Camp two days later.

Tomo Cesen claimed he climbed the South-southeast spur to the Shoulder solo on August 4, 1986 in just 19 hours. Excerpt from Climbing The World's 14 Highest Mountains by Richard Sale and John Cleare: ... but did not attempt either the summit or Camp IV before descending the Abruzzi Spur. The climb was controversial because Cesen claimed a new route, though virtually (actually?) all of it had been climbed by Scott's team in 1983, and many doubted his claim.

In 1994 a strong Spanish team completed the south-southeast spur all the way to the summit, with Alberto and Felix Inurrategi, Juanito Oiarzabal, Enríque de Pablo, and Juan Tomas reaching the K2 summit on June 24, 1994. According to the Spanish, this route is easier than the Abruzzi Ridge.